By Dr. Petrus Raulino

The impact of seasonality

Seasonal rhythms profoundly affect mood. Negative affect, including depression, anger and hostility, reaches its lowest level in summer, while rates of seasonal affective disorder peak during the winter months.

Some people feel less cheerful and upbeat with the arrival of colder seasons, such as fall or winter. What almost nobody knows is that these characteristics can actually be symptoms of a type of depression: seasonal depression.

Light and neurotransmitters

Research has shown that neurotransmitter levels can be affected according to the brightness of the time of year.

For example, the length of the day can influence neurotransmitter levels. A long day increases serotonin and noradrenaline levels in the brain in mice and reduces depression and anxiety behavior, compared to a short day.

The duration of exposure to daylight is similarly associated with the flow of serotonin metabolism in the brain in humans.

If neurotransmitter levels can be affected by light, why not neuroreceptor systems?

Neuroreceptors

Research suggests that mood swings over time may be mediated by phases of slow changes in different neuroreceptor systems.

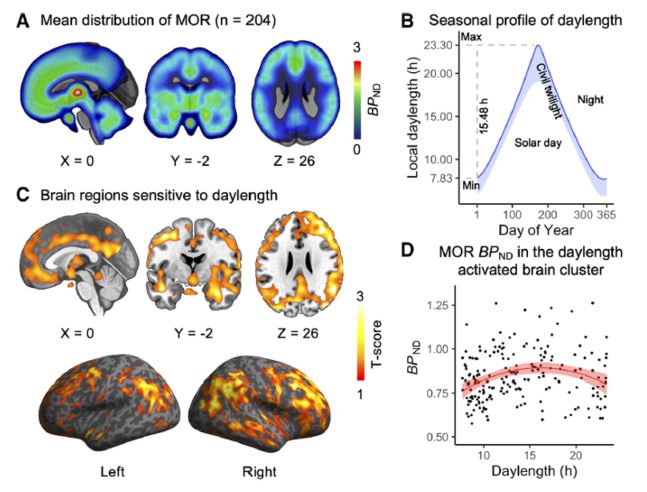

A study carried out at the University of Turku in Finland and published in The Journal of Neuroscience compared how the length of the day affected opioid receptors in humans and rats.

Opioid receptors are cellular receptors for neurotransmitters present in the nervous system. Opioids, whether endogenous (produced by the body itself) or exogenous, bind specifically and reversibly to these receptors, thus producing their biological actions.

The close link between seasonal mood fluctuations and opioid neurotransmission suggested a potential seasonal variation in opioid receptor signaling related to human emotions in vivo.

The research concluded that seasonal variation in day length influenced the availability of opioid receptors in the brain, following an inverted U-shaped curve in humans and rats.

Given the links between opioid receptor signaling and socio-emotional behavior, the research findings suggest that the opioid receptor system may represent a biological basis for seasonal variation in human mood and social behavior.

The opioid receptor system could be a viable target for the treatment of seasonal affective disorder, but there is still a long way to go for future research.

In any case, the study had the merit of demonstrating yet another element of the biological basis of seasonal mood.

References

Sun, L., Tang, J., Liljenbäck, H., Honkaniemi, A., Virta, J., Isojärvi, J., ... & Nummenmaa, L. (2021). Seasonal Variation in the Brain ?-Opioid Receptor Availability. Journal of Neuroscience, 41(6), 1265-1273.

Lutz, P. E., Courtet, P., & Calati, R. (2020). The opioid system and the social brain: implications for depression and suicide. Journal of neuroscience research, 98(4), 588-600.

Becker, J. A., Clesse, D., Spiegelhalter, C., Schwab, Y., Le Merrer, J., & Kieffer, B. L. (2014). Autistic-like syndrome in mu opioid receptor null mice is relieved by facilitated mGluR4 activity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(9), 2049-2060.

Harmatz, M. G., Well, A. D., Overtree, C. E., Kawamura, K. Y., Rosal, M., & Ockene, I. S. (2000). Seasonal variation of depression and other moods: a longitudinal approach. Journal of biological rhythms, 15(4), 344-350.

Lam, R. W., & Levitan, R. D. (2000). Pathophysiology of seasonal affective disorder: a review. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 25(5), 469.